Estonian President to Award Neeme Järvi

Ahead of Independence Day, President Alar Karis will award a record 203 state decorations to Estonians across diverse fields and supporters abroad.

"These state decorations recognize people from a variety of fields at home, as well as our friends and supporters abroad, for their dedication and care in their professional work or community," Karis wrote in the preface to his order.

President Karis is awarding the Order of the National Coat of Arms, 1st Class to Estonian-American conductor Neeme Järvi for his outstanding contributions to Estonian music culture.

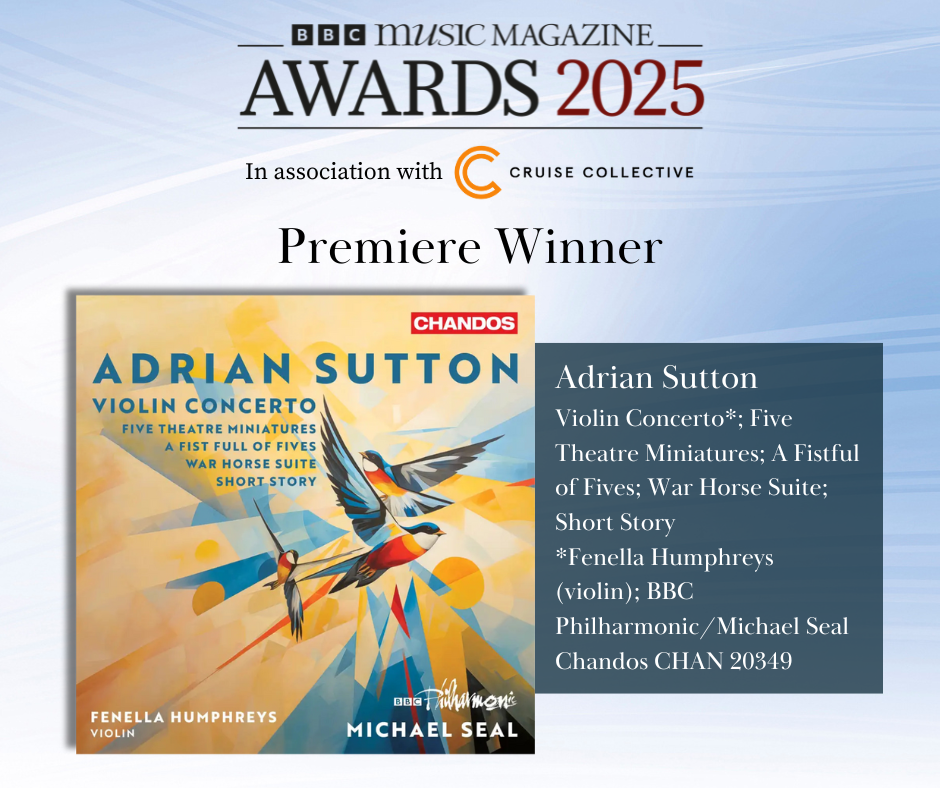

BBC Music Magazine Awards 2026

We're delighted to share that two of our albums have been nominated for a BBC Music Magazine award in the Concerto and Opera categories.

Please take a minute to vote for each album. It's quick and easy. Click the links below, scroll to the bottom of the page to find the poll, then submit your vote! We truly appreciate your support.

Vote for Walton - Cello Concerto

RPS Awards

2026 Royal Philarmonic Society Awards shortlists announced

Among the star names shortlisted are John Wilson, the conductor and Artistic Director for the Sinfonia of London, Matilda Lloyd, described by BBC Music Magazine as a “trumpeter extraordinaire”, and Peter Moore who in 2008, aged just 12, won the televised final of BBC Young Musician. Now, he becomes the first trombone player to be shortlisted for the RPS Instrumentalist Award.

,%20by%20chris%20christodoulou.jpg)

Presto Music Awards 2025

'Each year, we choose our 100 favourite recordings released across the previous 12 months. From this shortlist, we carefully select our Top 10 Recordings of the Year - the recordings which really made us listen with fresh ears to works we thought we already knew, or provided compelling advocacy for new discoveries!' - Presto Music

Orchestra of the Year - Gramophone Awards 2025

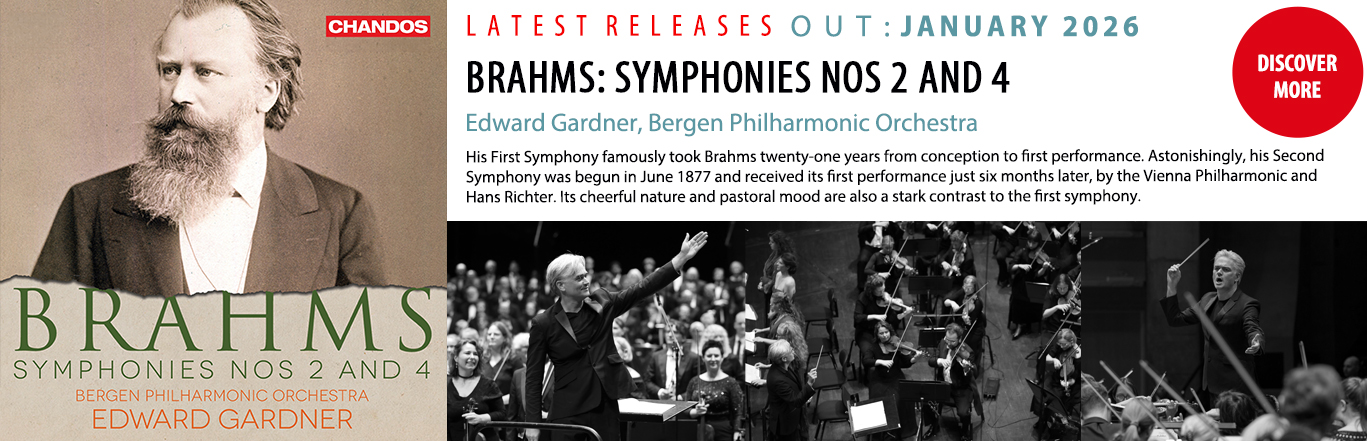

Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra have won a Gramophone award for Orchestra of the Year!

Created 260 years ago, this is an orchestra with local focus as well as international relevance – and it continues to evolve through a strong sense of tradition - Gramophone

Created 260 years ago, this is an orchestra with local focus as well as international relevance – and it continues to evolve through a strong sense of tradition - Gramophone

Matilda Lloyd & Richard Gowers | Fantasia

Fantasia, the new album from Matilda Lloyd and Richard Gowers, is out on September 19th!

Here is the latest video on Matilda's YouTube channel, where Matilda Lloyd and Richard Gowers perform Adagio in A minor BWV 564 by Johann Sebastian Bach arr. Richard Gowers, which is the third single from the album.

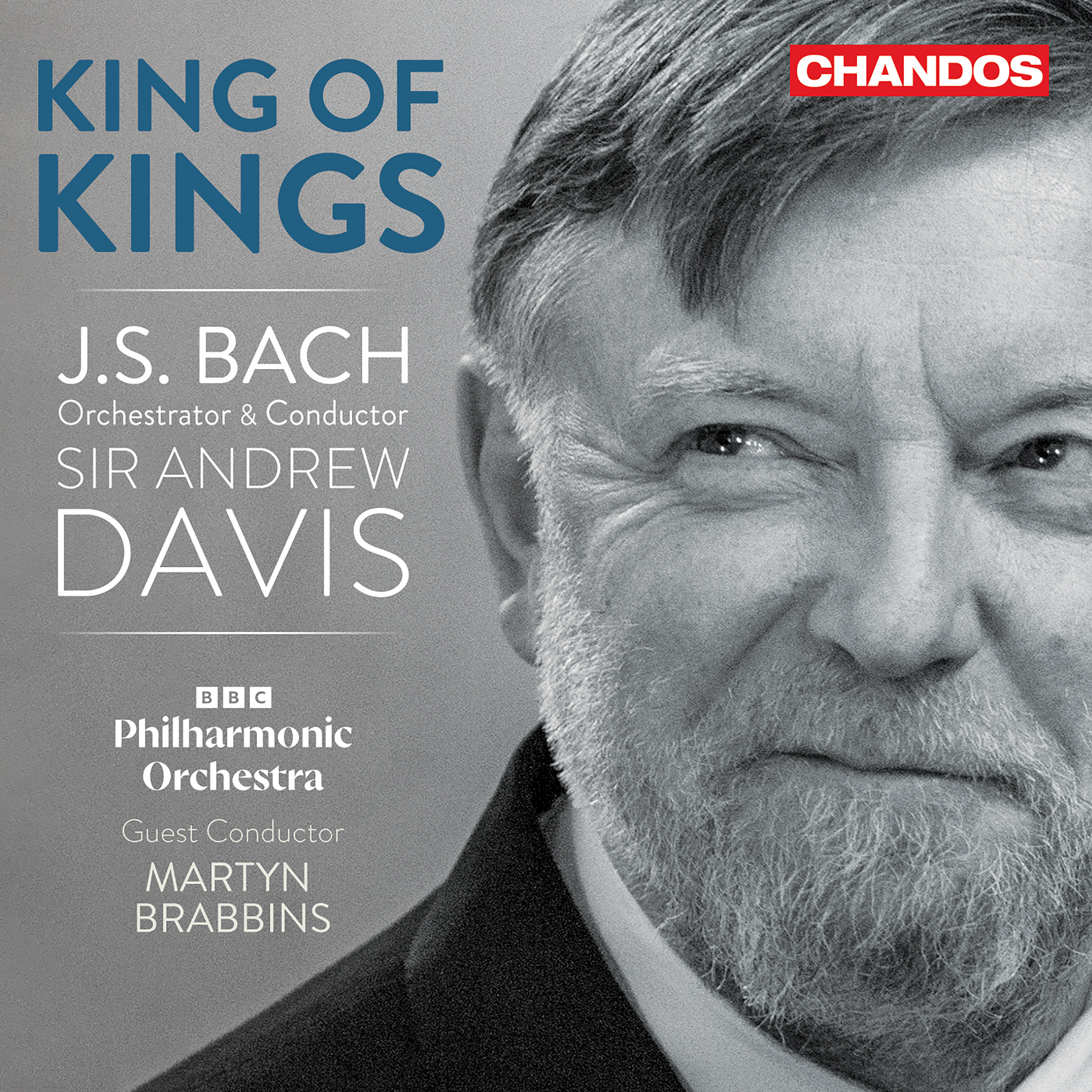

King of Kings | Sir Andrew Davis

Big news! King of Kings is No. 1 in the Specialist Classical Chart, and has been selected as Gramophone's Recording of the Month!

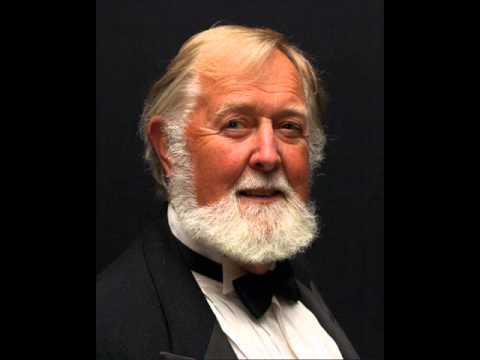

Sir Roger Norrington

We are saddened by the news of the death of the esteemed conductor and musicologist Sir Roger Norrington, who passed away on Saturday 18th July aged 91. Throughout his long and successful career a Sir Roger was a true pioneer, driven to unveil the composer's original intention in every score that he studied. His final recordings - the Mozart Violin Concertos with Francesca Dego for Chandos - are as much an example of this dedication as were his ground-breaking Beethoven Symphony recordings of the 1980s & 90s. Our thoughts are with his family and friends at this time.

Gramophone's Orchestra of the Year 2025

Brilliant news! Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and BBC Symphony Orchestra have been nominated for Gramphone's Classical Music Awards 2025.

This is the only Gramphone award decided by public vote, so your vote really does matter.

Gramophone's Recording of the Month

“A passionate, powerful account of Strauss’s great opera, with sumptuous orchestral playing and a dramatically astute cast”

Salome, the new album from Edward Gardner and the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra has been selected as Gramophone Magazine's Recording of the Month!

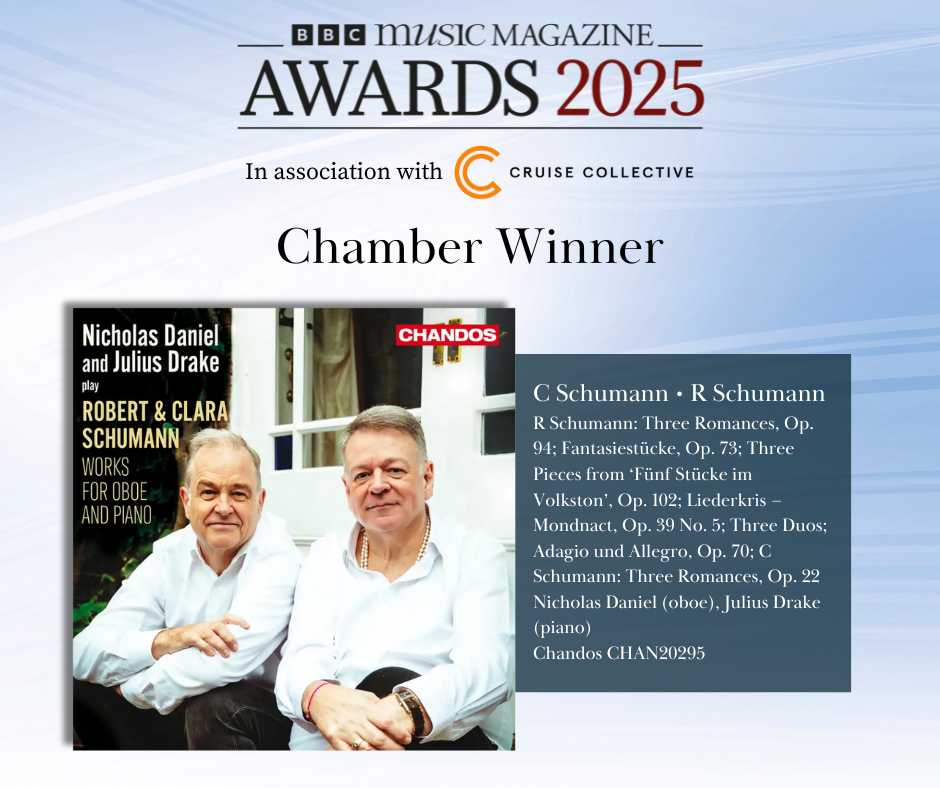

BBC Music Magazine Awards 2025

WINNER! RPS Awards

Congratulations to the wonderful cellist Laura van der Heijden who has won The Intrumentallist Award at the 2025 Royal Philharmonic Society Awards!

Juanjo Mena Shares Health Update

Watch Juanjo's video update on Instagram or X/Twitter.

The Chandos team send our best wishes to conductor Juanjo Mena following his recent Alzheimer's Disease diagnosis. We look forward to working with him soon!

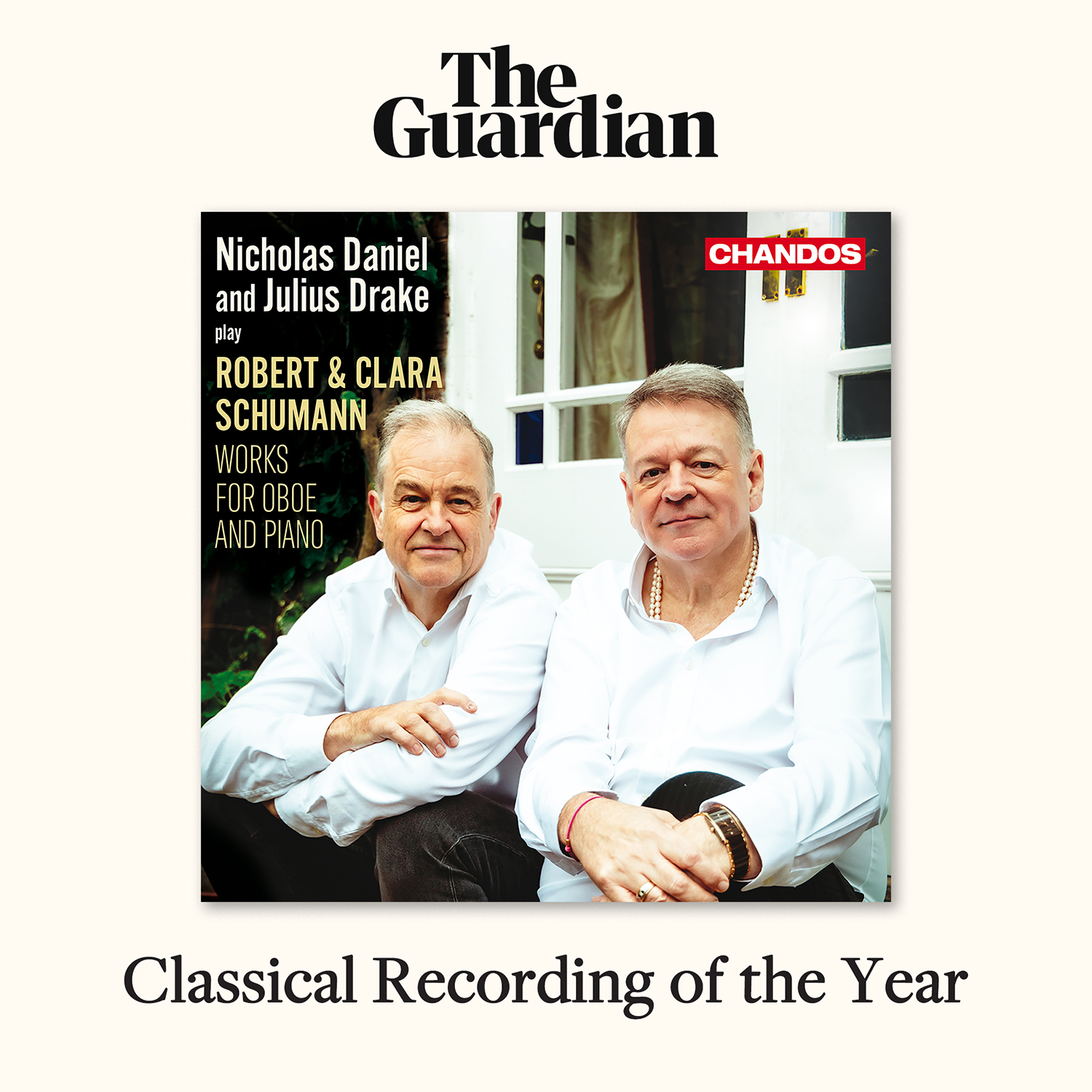

The Guardian Classical Recording of the Year

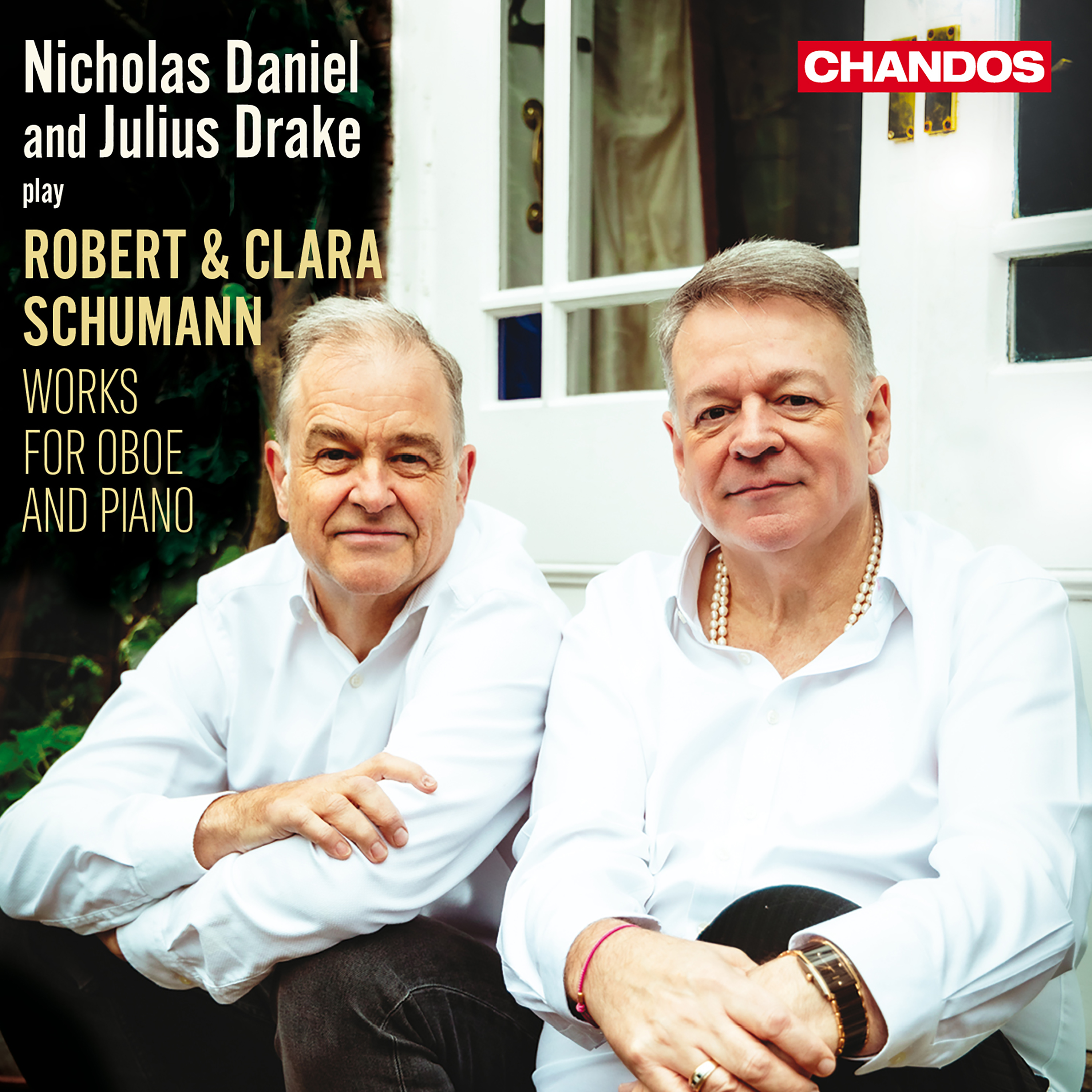

Nicholas Daniel and Julius Drake's latest album, Schumann: Works for Oboe and Piano, has been named as one of The Guardian's top recordings of 2024!

“Pure delight from first note to last.”

Classical Winner - Presto Music Awards 2024

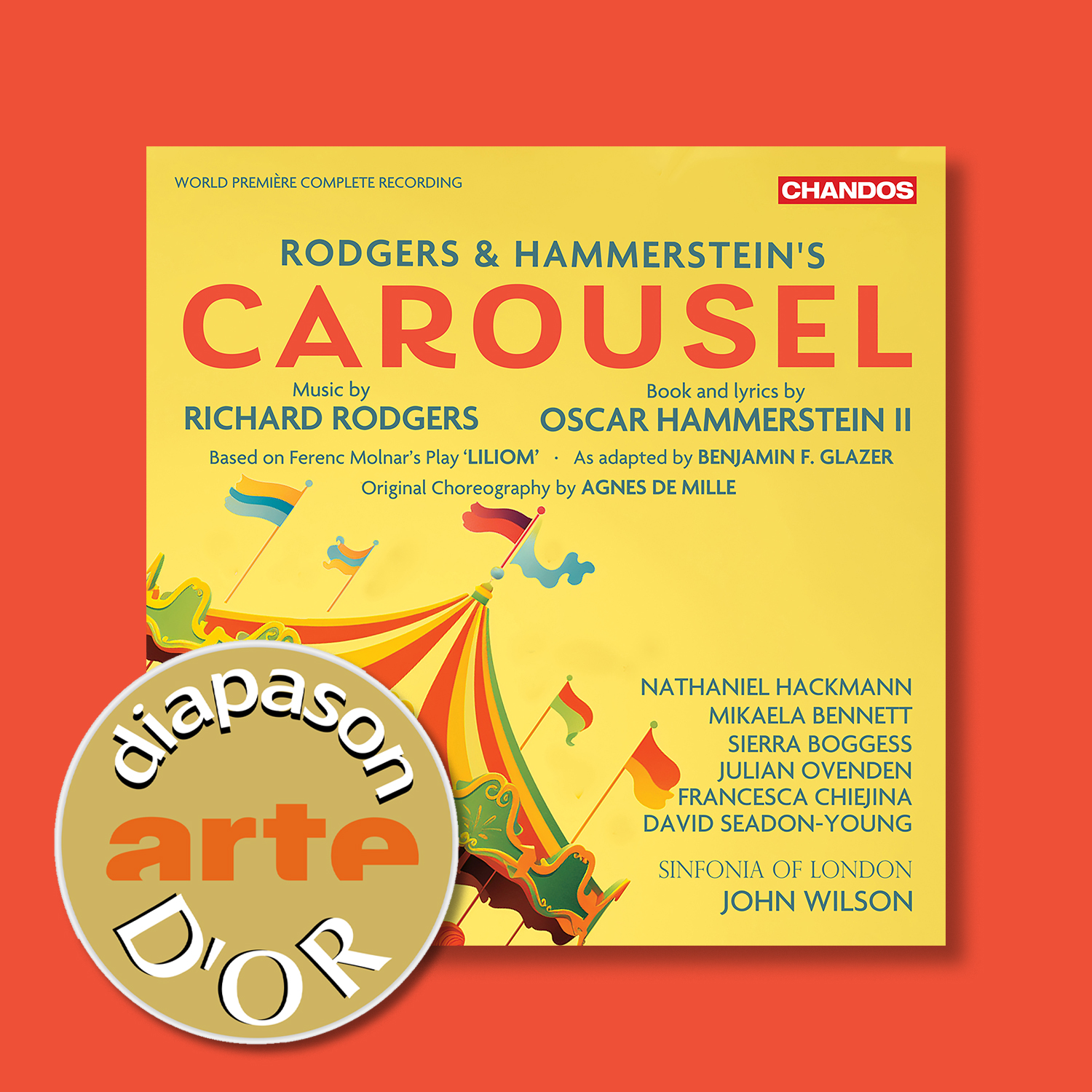

Fantastic news! Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel has been awarded Classical Winner in Presto Music's Top 10 Recordings of 2024.

Diapason D'Or Arte Award

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel from John Wilson and Sinfonia of London has been awarded the Diapason D'Or Arte in Diapason's December issue!

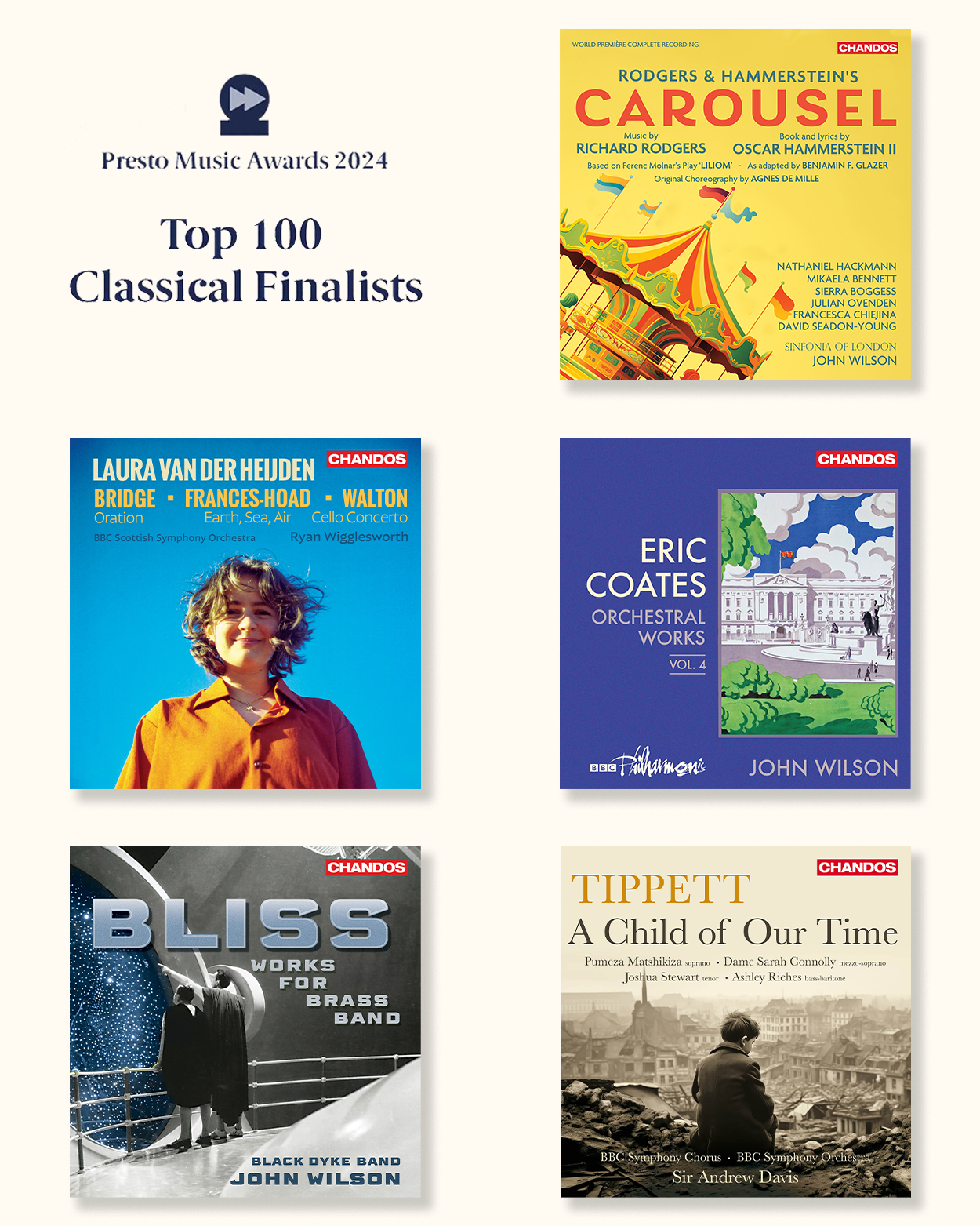

Presto Music Awards 2024

We have five recordings in Presto Music's Top 100 Classical Recordings 2024! The Top 10 recordings and the winners in six special award categories will be announced on the evening of Thursday 5th December.

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel

Bridge/Walton/Frances-Hoad: Cello Concertos

Eric Coates Orchestral Works, Vol. 4

ICMA Awards 2025

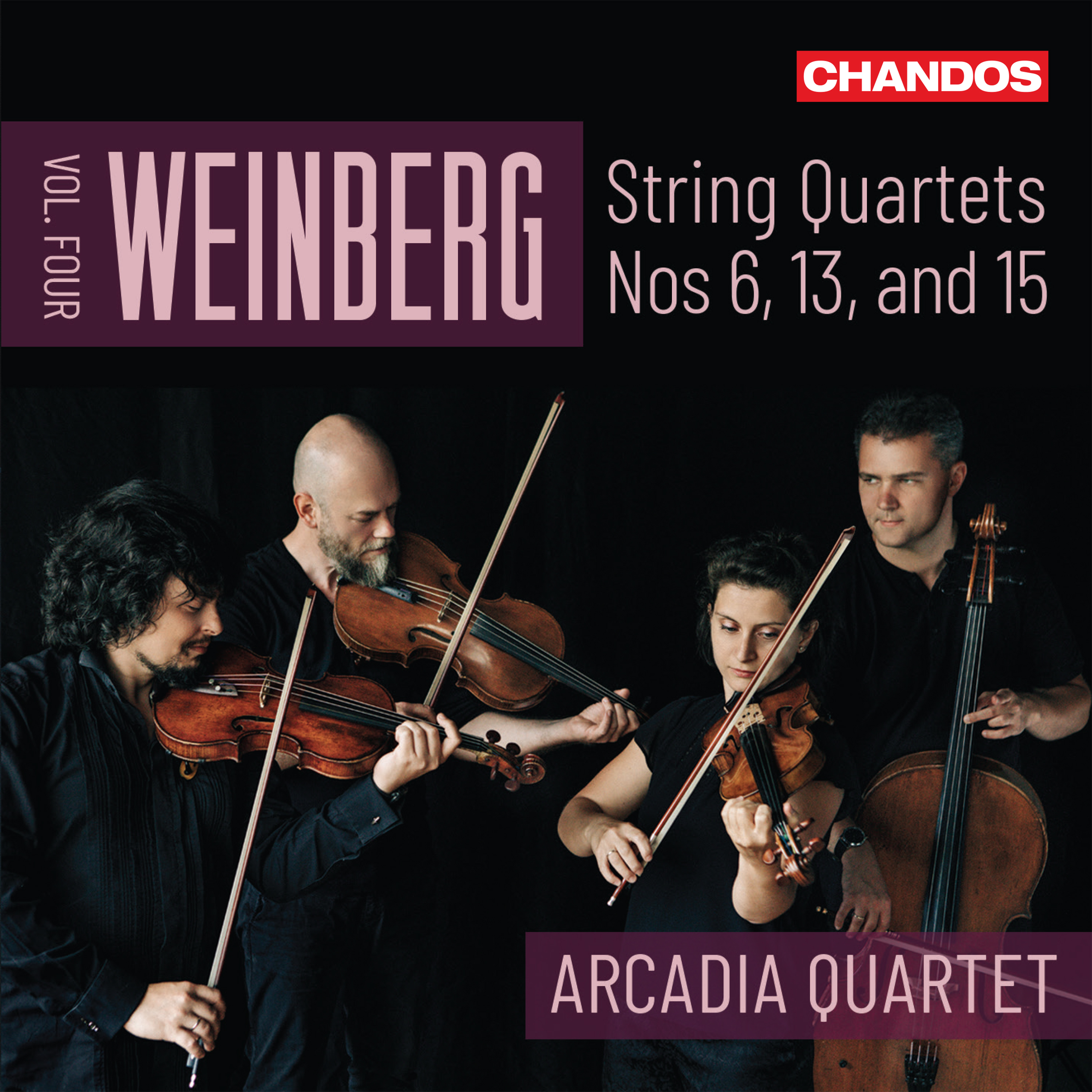

Chandos has four nominations in the Symphonic Music and Chamber categories of the International Classical Music Awards 2025!

Nominated in the Symphonic Music category

Nominated in the Chamber category

Nominated in the Chamber category

Nominated in the Chamber category

Download Service has closed

Chandos Records sincerely thanks our loyal digital download customers for their support over the last 20 years. Due to the continuous decline in the popularity of digital downloads, ‘The Classical Shop’ will be closed for all digital download services on 29th November.

Our website is now dedicated to exclusive news, special offers and information about Chandos label and artists:CD and SACD sales will continue as usual. We are excited for the next chapter!

RIP Benjamin Luxon

One of Britain’s finest international singers, Benjamin Luxon, died on the 25th July aged 87. Born in Redruth, Cornwall, Luxon began his career as a member of the English Opera Group, the company formed by Benjamin Britten for the performance of his own and other contemporary operas. Luxon became one of Britten’s key singers and the composer wrote the role of “Owen Wingrave” specifically for Luxon’s voice. Luxon became an important singer internationally, performing at the Royal Opera House, Glyndebourne, Tanglewood, the Teatro alla Scala, Paris Opera, Oper Frankfurt, Wiener Staatsoper, and the Metropolitan Opera. He went on to work with some of the most important conductors and orchestras and made over 100 recordings, including many for Chandos. Luxon was made a Commander of the British Empire (CBE) in 1986 for his service to music.

RIP Sir Andrew Davis

We are saddened by the news that Sir Andrew Davis, the renowned British conductor, passed away peacefully on Saturday, April 20, 2024, surrounded by family after a battle with leukaemia. Sir Andrew recorded exclusively for Chandos Records from his first album Elgar’s Crown of India in 2009, making almost 50 recordings and gathering countless accolades and awards in the process. We will miss a wonderful musician who imparted so much to all who worked with him in such a generous, self-deprecating and humble way. RIP Andrew.

Sir Andrew Davis's obituary

Neave Trio

25% discount on Neave Trio Recordings

Hailed by the magazine BBC Music for its ‘generous and warm-hearted, utterly beguiling playing’, the GRAMMY®-nominated Neave Trio has emerged as one of the finest young ensembles of its generation. Its members originating from the US, Russia, and Japan, the Trio has performed on concert stages from Carnegie Hall, in New York, to venues in the UK, continental Europe, Japan, and Russia, bringing audiences to their feet and receiving the highest critical acclaim. Performances have been broadcast on radio stations across the United States and abroad, notably on American Public Media’s Performance Today. Previous recordings have been met with critical acclaim, listed among ‘The Best New Recordings of 2018 (So Far)’ on WQXR and among the best recordings of 2019 both by The New York Times and BBC Radio 3. The Trio’s 2022 album, Musical Remembrances, was nominated for a GRAMMY® in the Best Chamber Music / Small Ensemble category.

Editor's Choice

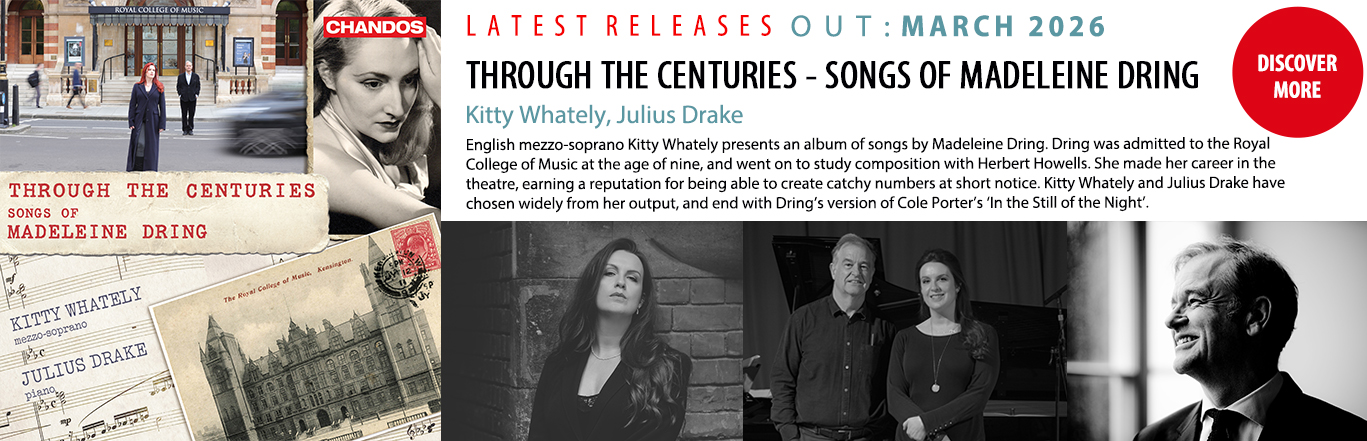

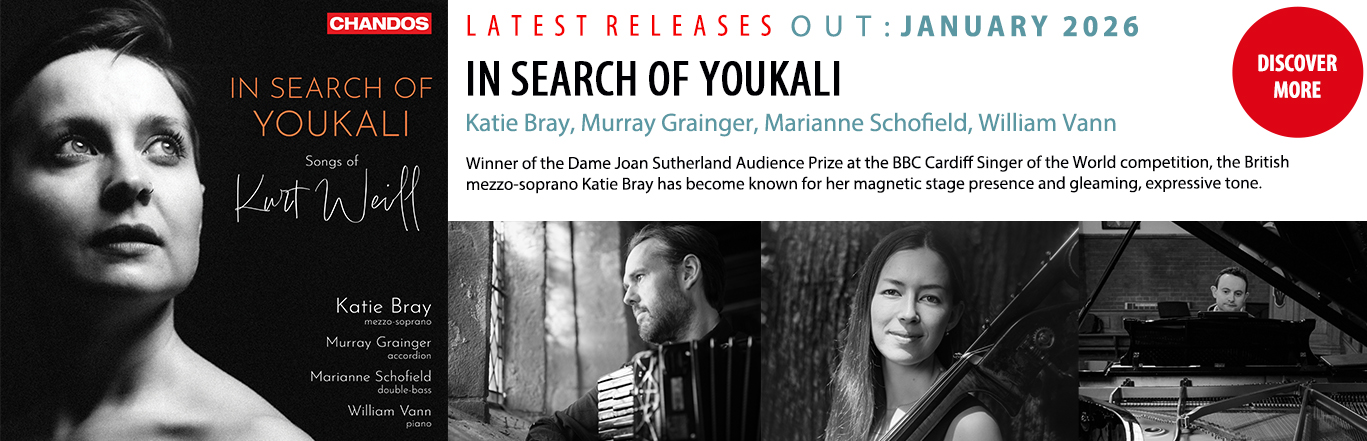

'Katie Bray’s Weill odyssey is as powerful as it is poignant.'

Editor's Choice

'Katie Bray’s Weill odyssey is as powerful as it is poignant.'

'The Rondo in C minor, Op 1, written while Chopin was studying with Józef Elsner and published in Warsaw in 1825, is a virtuosic display in the brilliant style. Lortie plays it with a light touch and Mozartian esprit.'

'The Rondo in C minor, Op 1, written while Chopin was studying with Józef Elsner and published in Warsaw in 1825, is a virtuosic display in the brilliant style. Lortie plays it with a light touch and Mozartian esprit.'

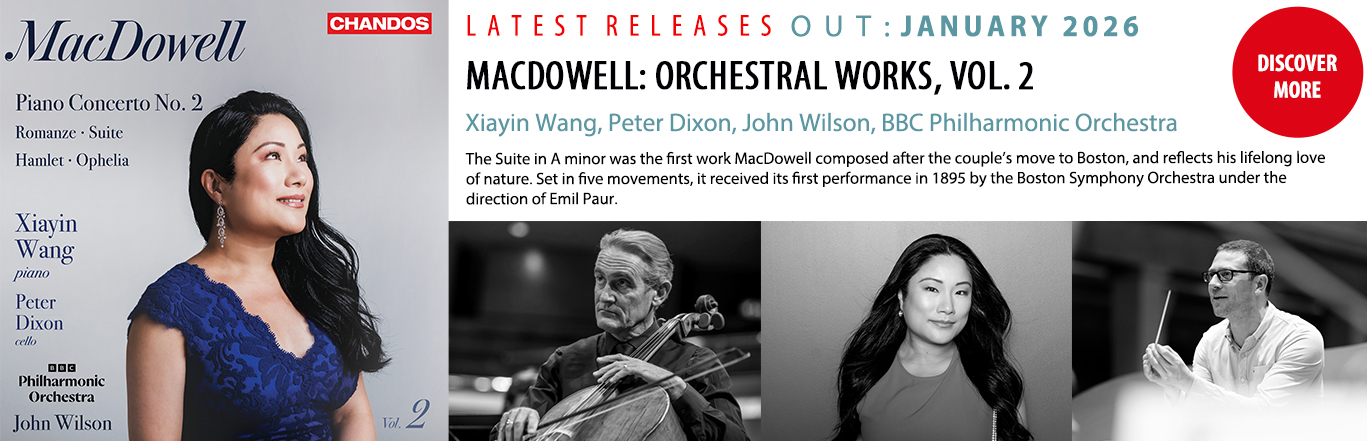

Concerto Choice

'In John Wilson's hands, Walton's Ravelian timbres shimmer and glisten.'

Concerto Choice

'In John Wilson's hands, Walton's Ravelian timbres shimmer and glisten.'

Editor's Choice

'If ever there were a composer and conductor ideally suited to each other, it is William Walton and John Wilson.'

Editor's Choice

'If ever there were a composer and conductor ideally suited to each other, it is William Walton and John Wilson.'

My Wish List

My Wish List

,%20by%20kaupo%20kikkas.jpg)

.jpg)

,%20by%20richard%20hubert%20smith.jpg)