Presto Music Awards 2025

'Each year, we choose our 100 favourite recordings released across the previous 12 months. From this shortlist, we carefully select our Top 10 Recordings of the Year - the recordings which really made us listen with fresh ears to works we thought we already knew, or provided compelling advocacy for new discoveries!' - Presto Music

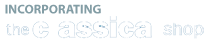

Orchestra of the Year - Gramophone Awards 2025

Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra have won a Gramophone award for Orchestra of the Year!

Created 260 years ago, this is an orchestra with local focus as well as international relevance – and it continues to evolve through a strong sense of tradition - Gramophone

Created 260 years ago, this is an orchestra with local focus as well as international relevance – and it continues to evolve through a strong sense of tradition - Gramophone

Matilda Lloyd & Richard Gowers | Fantasia

Fantasia, the new album from Matilda Lloyd and Richard Gowers, is out on September 19th!

Here is the latest video on Matilda's YouTube channel, where Matilda Lloyd and Richard Gowers perform Adagio in A minor BWV 564 by Johann Sebastian Bach arr. Richard Gowers, which is the third single from the album.

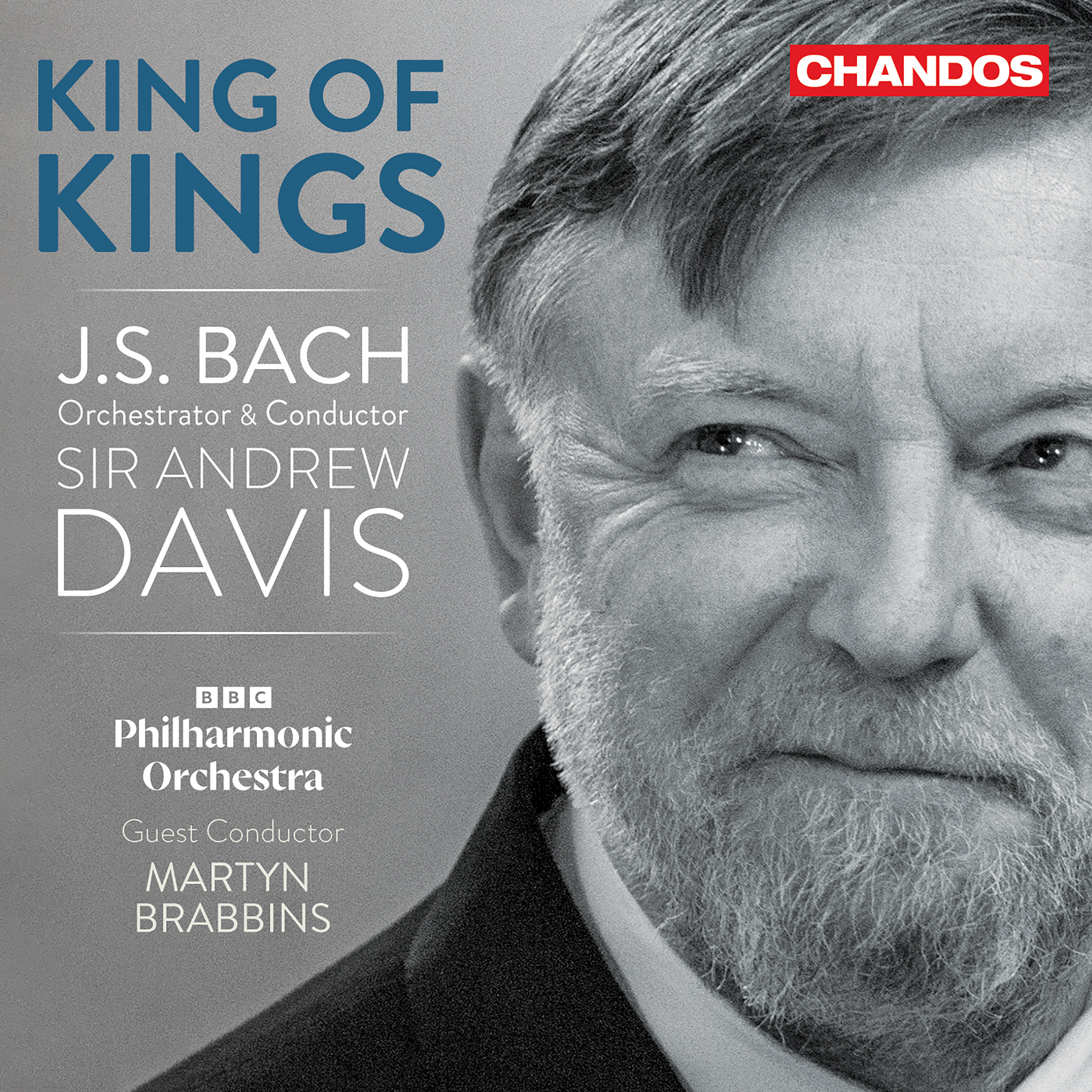

King of Kings | Sir Andrew Davis

Big news! King of Kings is No. 1 in the Specialist Classical Chart, and has been selected as Gramophone's Recording of the Month!

Sir Roger Norrington

We are saddened by the news of the death of the esteemed conductor and musicologist Sir Roger Norrington, who passed away on Saturday 18th July aged 91. Throughout his long and successful career a Sir Roger was a true pioneer, driven to unveil the composer's original intention in every score that he studied. His final recordings - the Mozart Violin Concertos with Francesca Dego for Chandos - are as much an example of this dedication as were his ground-breaking Beethoven Symphony recordings of the 1980s & 90s. Our thoughts are with his family and friends at this time.

Gramophone's Orchestra of the Year 2025

Brilliant news! Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra and BBC Symphony Orchestra have been nominated for Gramphone's Classical Music Awards 2025.

This is the only Gramphone award decided by public vote, so your vote really does matter.

Gramophone's Recording of the Month

“A passionate, powerful account of Strauss’s great opera, with sumptuous orchestral playing and a dramatically astute cast”

Salome, the new album from Edward Gardner and the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra has been selected as Gramophone Magazine's Recording of the Month!

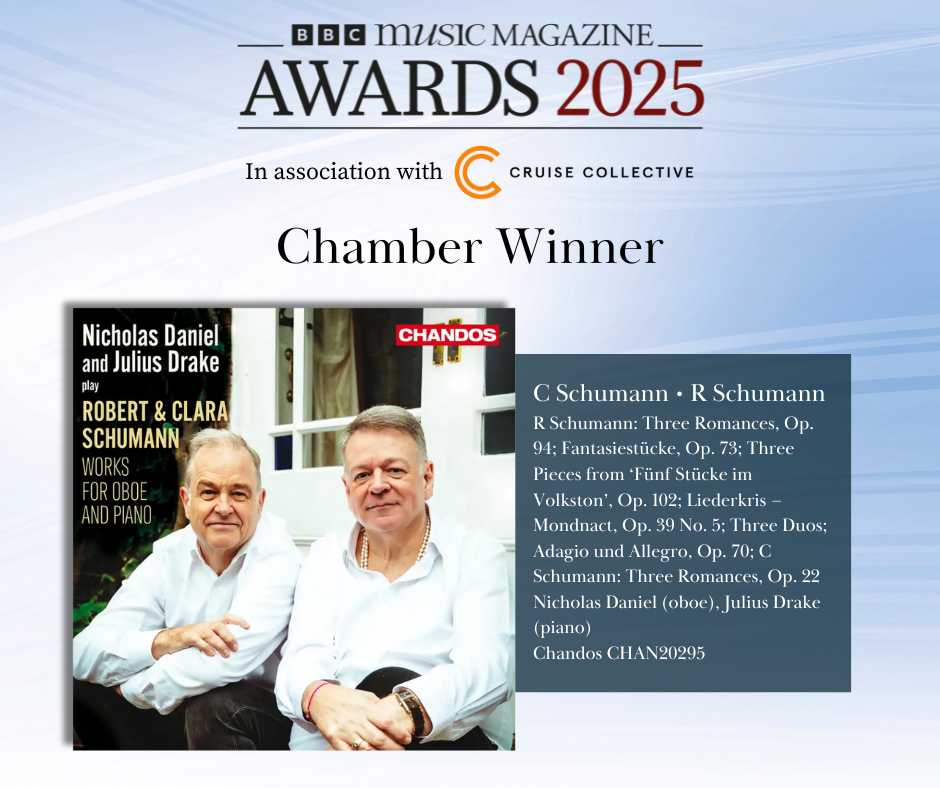

BBC Music Magazine Awards 2025

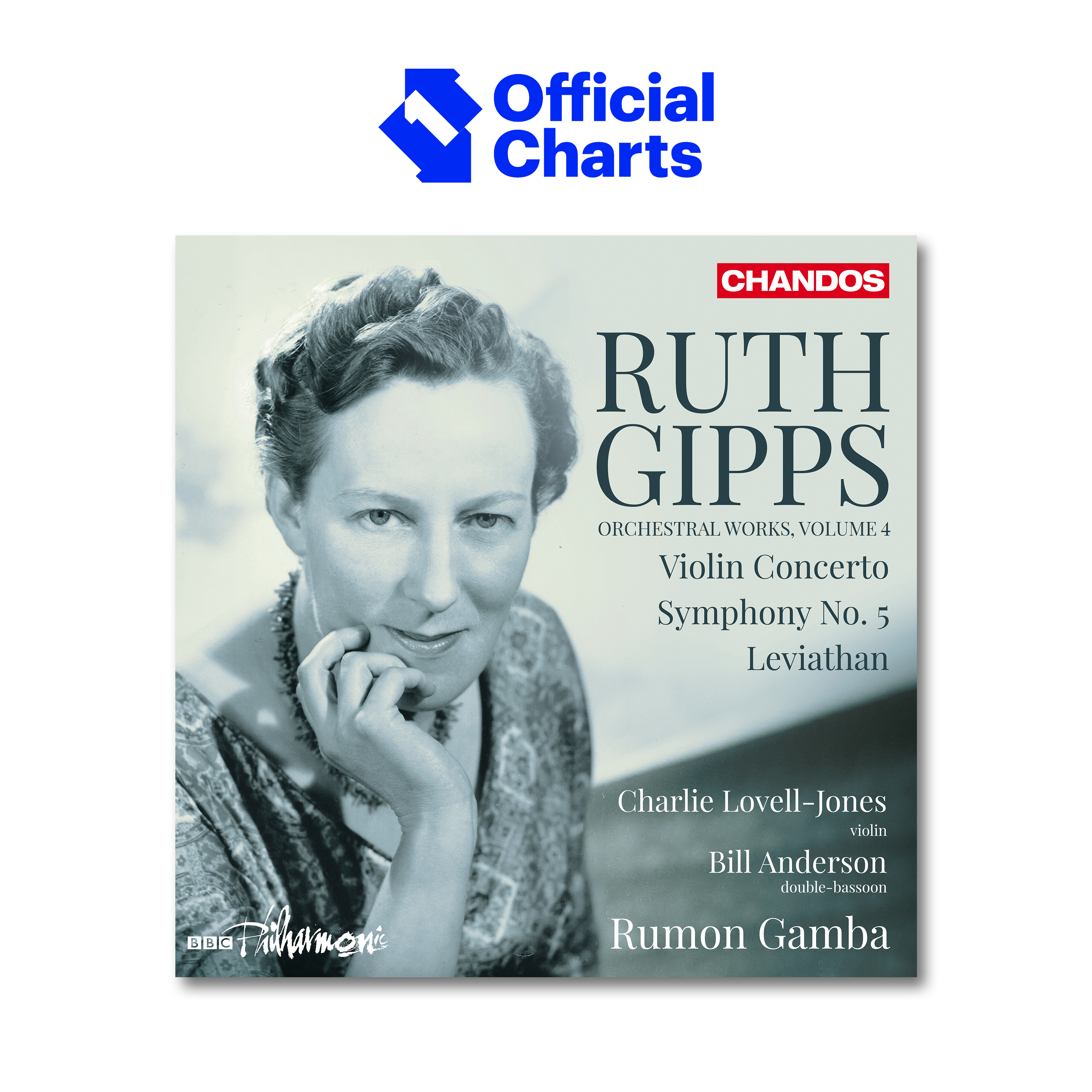

Great News! Another No. 1 Album...

Following in Volume 3's footsteps, Ruth Gipps: Orchestral Works Volume 4 is No. 1 in the Official Specialist Classical Chart! Congratulations to Rumon Gamba, BBC Philharmonic, Charlie-Lovell Jones and Bill Anderson.

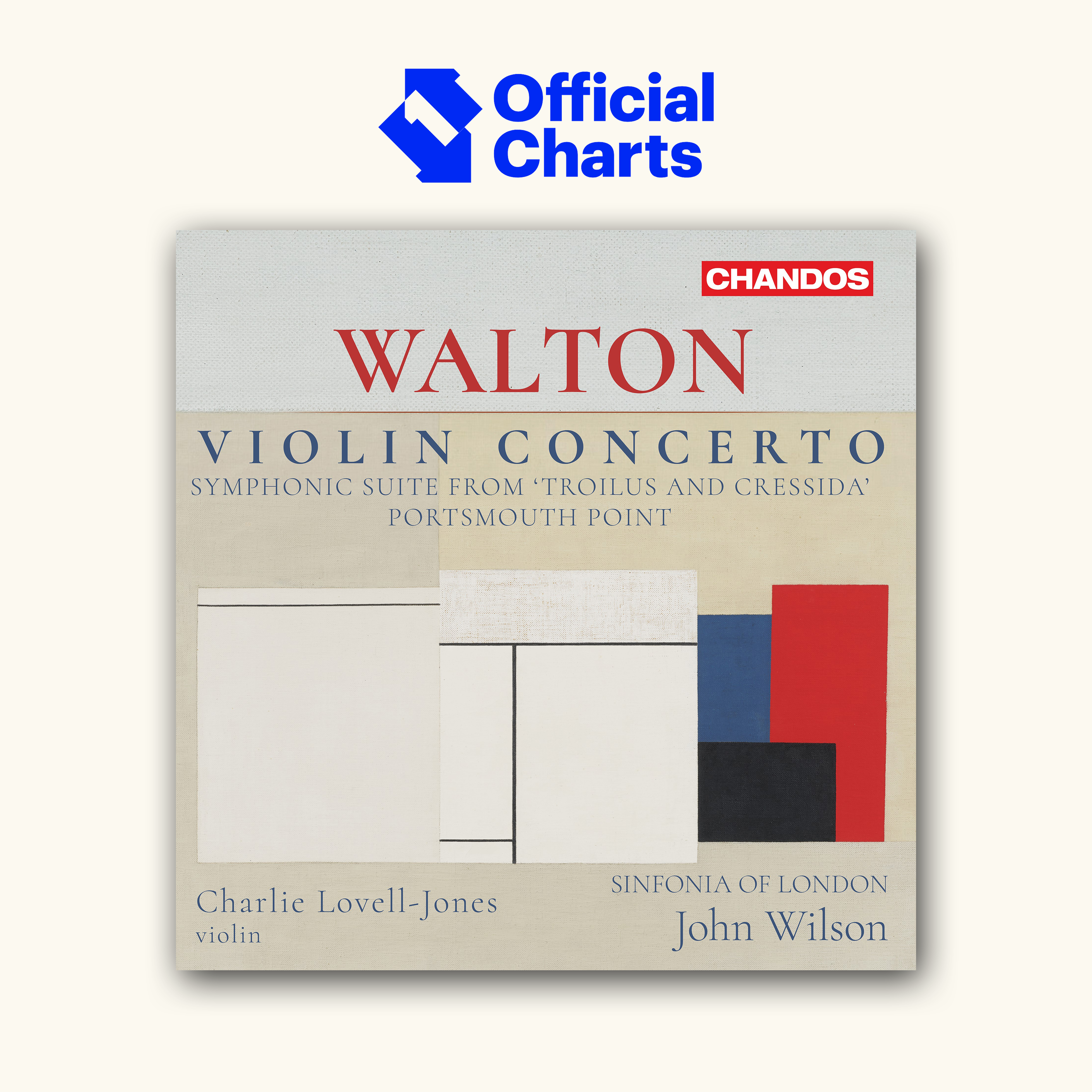

No. 1 Album! Walton: Violin Concerto

John Wilson and Sinfonia of London's new album with violinist Charlie Lovell-Jones has secured the number one spot in the Official Specialist Classical Chart!

WINNER! RPS Awards

Congratulations to the wonderful cellist Laura van der Heijden who has won The Intrumentallist Award at the 2025 Royal Philharmonic Society Awards!

Juanjo Mena Shares Health Update

Watch Juanjo's video update on Instagram or X/Twitter.

The Chandos team send our best wishes to conductor Juanjo Mena following his recent Alzheimer's Disease diagnosis. We look forward to working with him soon!

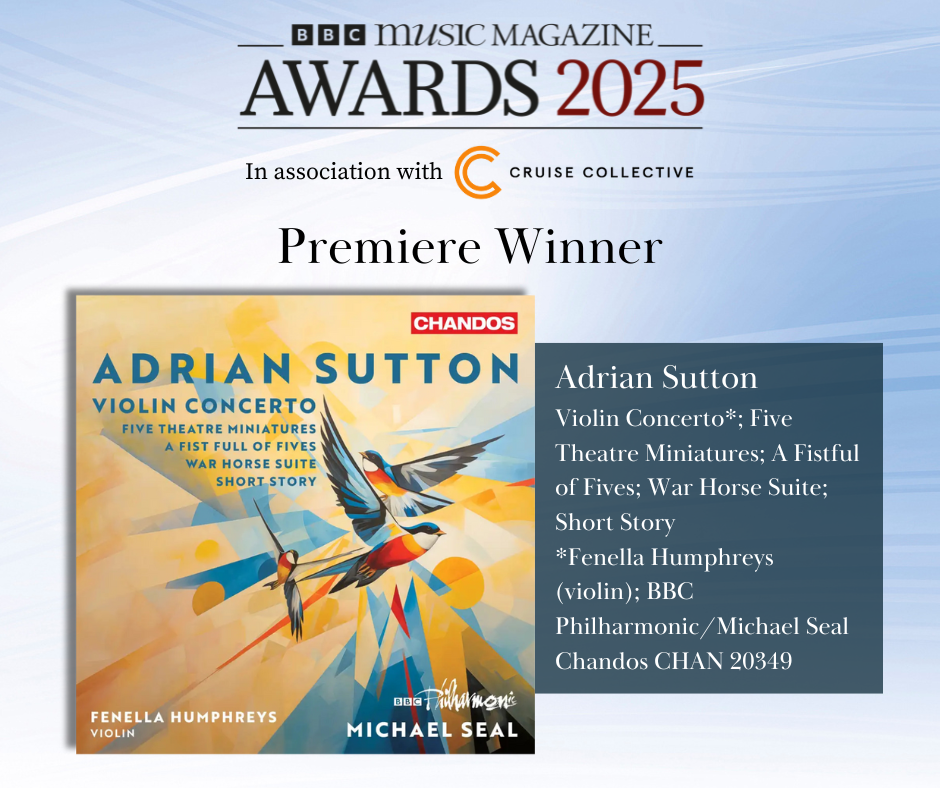

2025 BBC Music Magazine Awards

Big news! We have two nominations in the 2025 BBC Music Magazine Awards!

Schumann: Works for Oboe and Piano from Nicholas Daniel and Julius Drake is up for a Chamber Award, and Adrian Sutton's Violin Concerto, with Fenella Humphreys, Michael Seal and BBC Philharmonic, is a Premiere Nominee.

Please vote for the recordings here!

No.1 in the Specialist Classical Chart

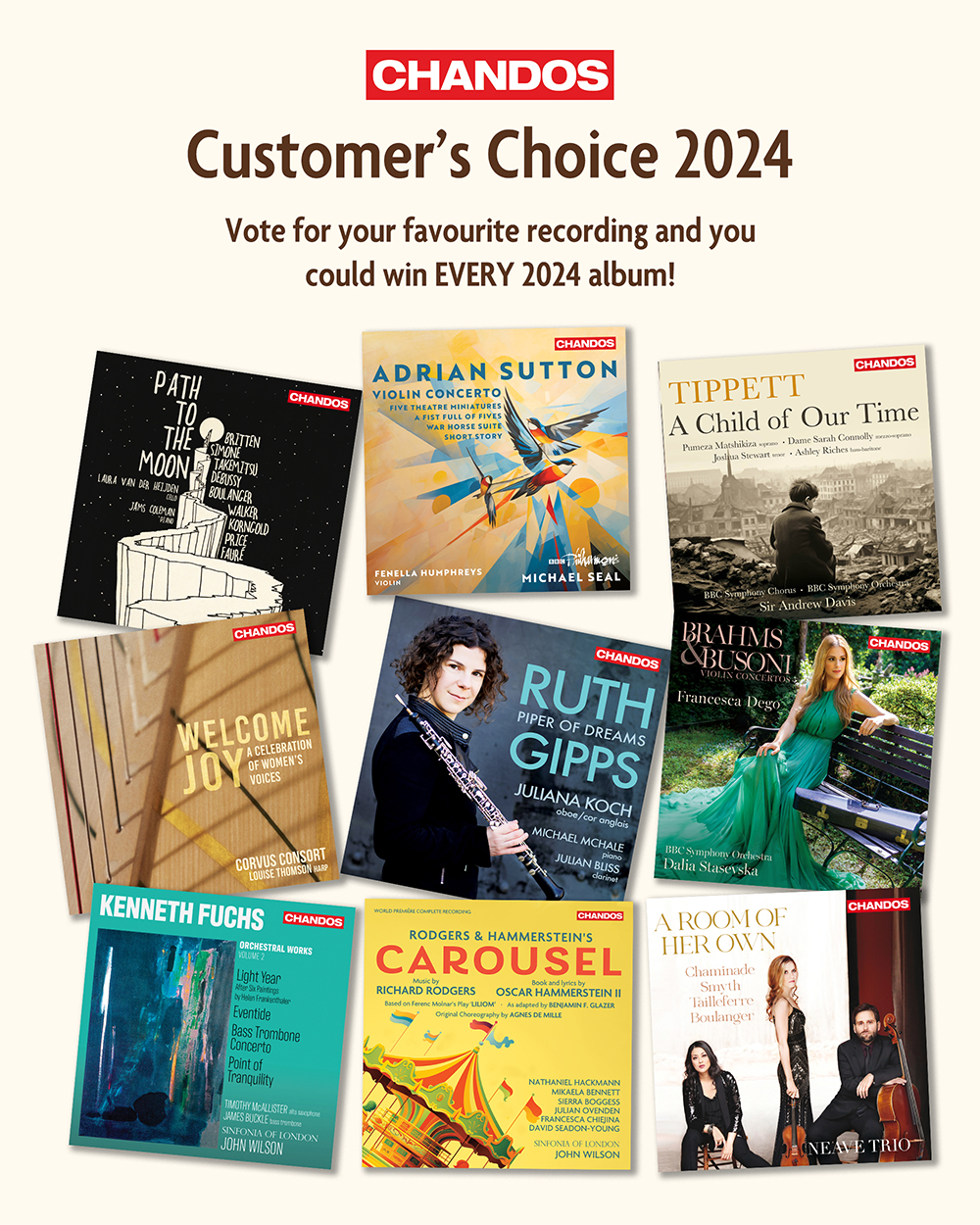

Customer's Choice Album of 2024

The votes are in for our Customer's Choice Album of 2024! Here are the top three albums...

WINNERS

1. Adrian Sutton: Orchestral Works

2. Sibelius: Works for Violin & Orchestra

3. Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel

VOTE NOW CLOSED! Keep an eye out on our social media platforms for the top voted album. All prize winners will be randomly selected and contacted shortly.

Vote closes 6th January at 4pm (GMT)

It's your last chance to vote for your favourite Chandos release of 2024.

You could win...

One person will win EVERY 2024 album. That's 45 CDs!

Five people will win all three January releases!

The Guardian Classical Recording of the Year

Nicholas Daniel and Julius Drake's latest album, Schumann: Works for Oboe and Piano, has been named as one of The Guardian's top recordings of 2024!

“Pure delight from first note to last.”

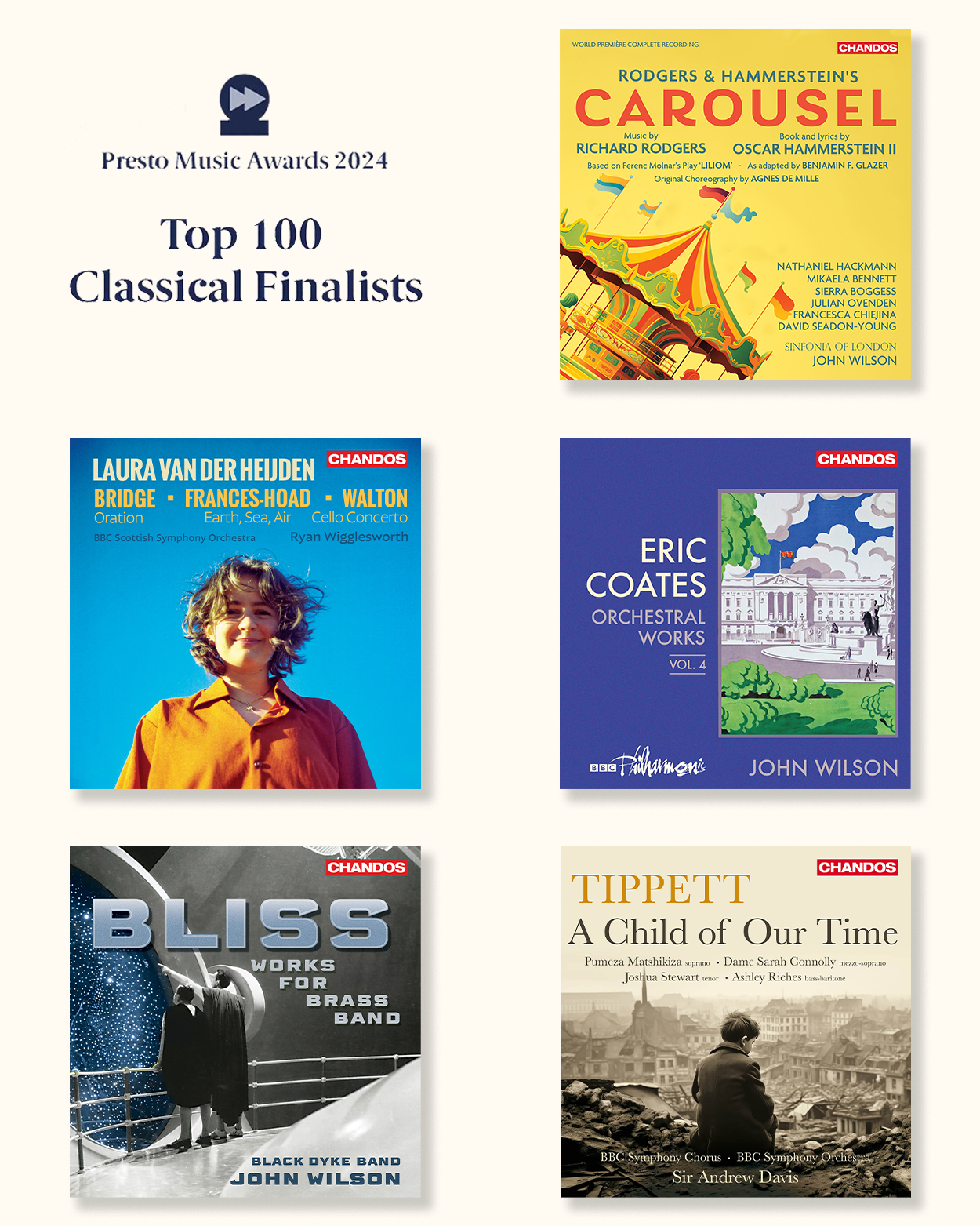

Classical Winner - Presto Music Awards 2024

Fantastic news! Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel has been awarded Classical Winner in Presto Music's Top 10 Recordings of 2024.

Diapason D'Or Arte Award

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel from John Wilson and Sinfonia of London has been awarded the Diapason D'Or Arte in Diapason's December issue!

Presto Music Awards 2024

We have five recordings in Presto Music's Top 100 Classical Recordings 2024! The Top 10 recordings and the winners in six special award categories will be announced on the evening of Thursday 5th December.

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel

Rodgers & Hammerstein's Carousel

Bridge/Walton/Frances-Hoad: Cello Concertos

Eric Coates Orchestral Works, Vol. 4

ICMA Awards 2025

Chandos has four nominations in the Symphonic Music and Chamber categories of the International Classical Music Awards 2025!

Nominated in the Symphonic Music category

Nominated in the Chamber category

Nominated in the Chamber category

Nominated in the Chamber category

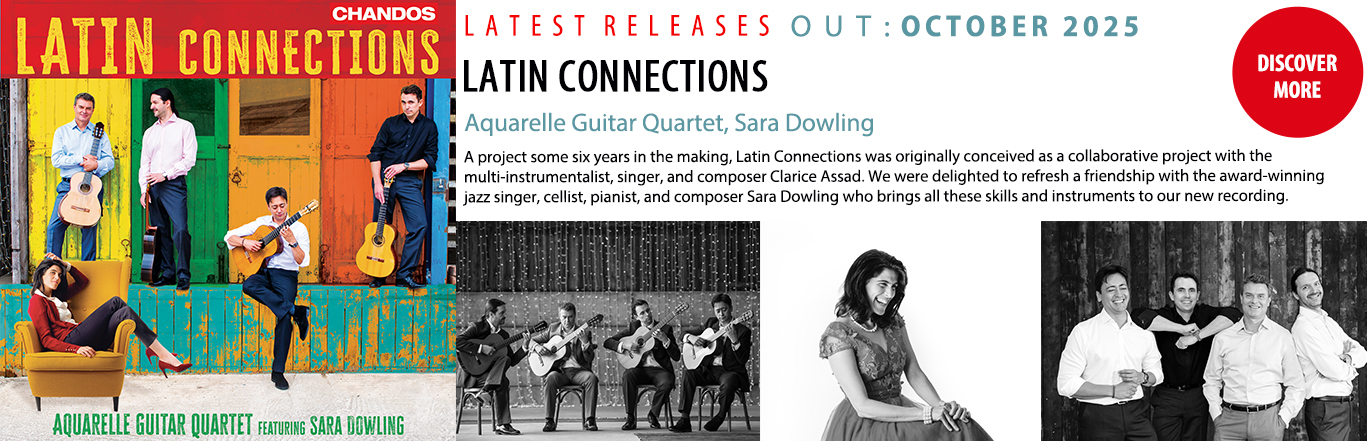

Release Spotlight

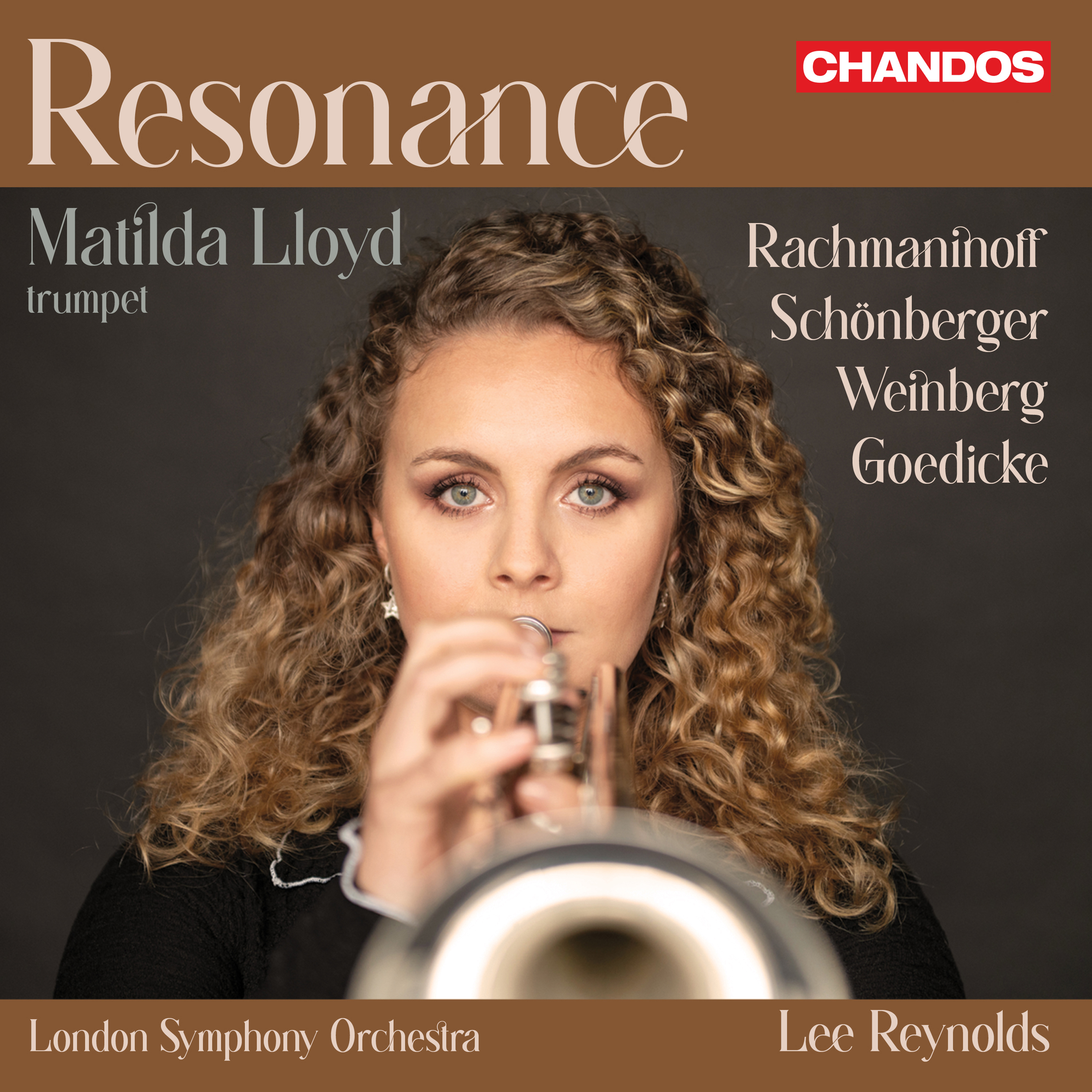

Trumpet virtuoso Matilda Lloyd is a true master of her instrument.

Matilda's second album with Chandos, featuring Weinberg's Trumpet Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra and Lee Reynolds, is out now.

'Resonance is a multi-faceted word with many different meanings, all of which are explored in this album of music for trumpet and orchestra.'

BBC Music Magazine

Fantastic news! Three Chandos albums have been featured in BBC Music Magazine's November and December issues.

Choral & Song - December Recording of the Month

Welcome Joy: A Celebration of Women's Voices receives a brilliant five star review. *****

"The 12 superb sopranos and altos of the Corvus Consort sing the complex, close-knit textures of these works with delicacy and pinpoint accuracy. Louise Thomson’s immaculate, virtuosic harp playing conjures scenes that take us from scented gardens to sun-baked landscapes and haunted moonlit forests. The vocal/instrumental balance is well-nigh perfect in Chandos’s clear, nuanced recording."

Orchestral Choice - December

Adrian Sutton's Violin Concerto secures the spot as December's Orchestral Choice. *****

"A colourful selection of imaginative new works"

Chamber - November Recording of the Month

Schumann: Works for Oboe and Piano obtains ***** from Rebecca Franks.

"Played with such warmth and eloquence, the arrangements chosen here often feel as if they were tailor-made for the instrument, while the sensitive programming paints a loving portrait of the Schumann household."

Download Service has closed

Chandos Records sincerely thanks our loyal digital download customers for their support over the last 20 years. Due to the continuous decline in the popularity of digital downloads, ‘The Classical Shop’ will be closed for all digital download services on 29th November.

Our website is now dedicated to exclusive news, special offers and information about Chandos label and artists:CD and SACD sales will continue as usual. We are excited for the next chapter!

RIP Benjamin Luxon

One of Britain’s finest international singers, Benjamin Luxon, died on the 25th July aged 87. Born in Redruth, Cornwall, Luxon began his career as a member of the English Opera Group, the company formed by Benjamin Britten for the performance of his own and other contemporary operas. Luxon became one of Britten’s key singers and the composer wrote the role of “Owen Wingrave” specifically for Luxon’s voice. Luxon became an important singer internationally, performing at the Royal Opera House, Glyndebourne, Tanglewood, the Teatro alla Scala, Paris Opera, Oper Frankfurt, Wiener Staatsoper, and the Metropolitan Opera. He went on to work with some of the most important conductors and orchestras and made over 100 recordings, including many for Chandos. Luxon was made a Commander of the British Empire (CBE) in 1986 for his service to music.

RIP Sir Andrew Davis

We are saddened by the news that Sir Andrew Davis, the renowned British conductor, passed away peacefully on Saturday, April 20, 2024, surrounded by family after a battle with leukaemia. Sir Andrew recorded exclusively for Chandos Records from his first album Elgar’s Crown of India in 2009, making almost 50 recordings and gathering countless accolades and awards in the process. We will miss a wonderful musician who imparted so much to all who worked with him in such a generous, self-deprecating and humble way. RIP Andrew.

Sir Andrew Davis's obituary

https://www.chandos.net/list/

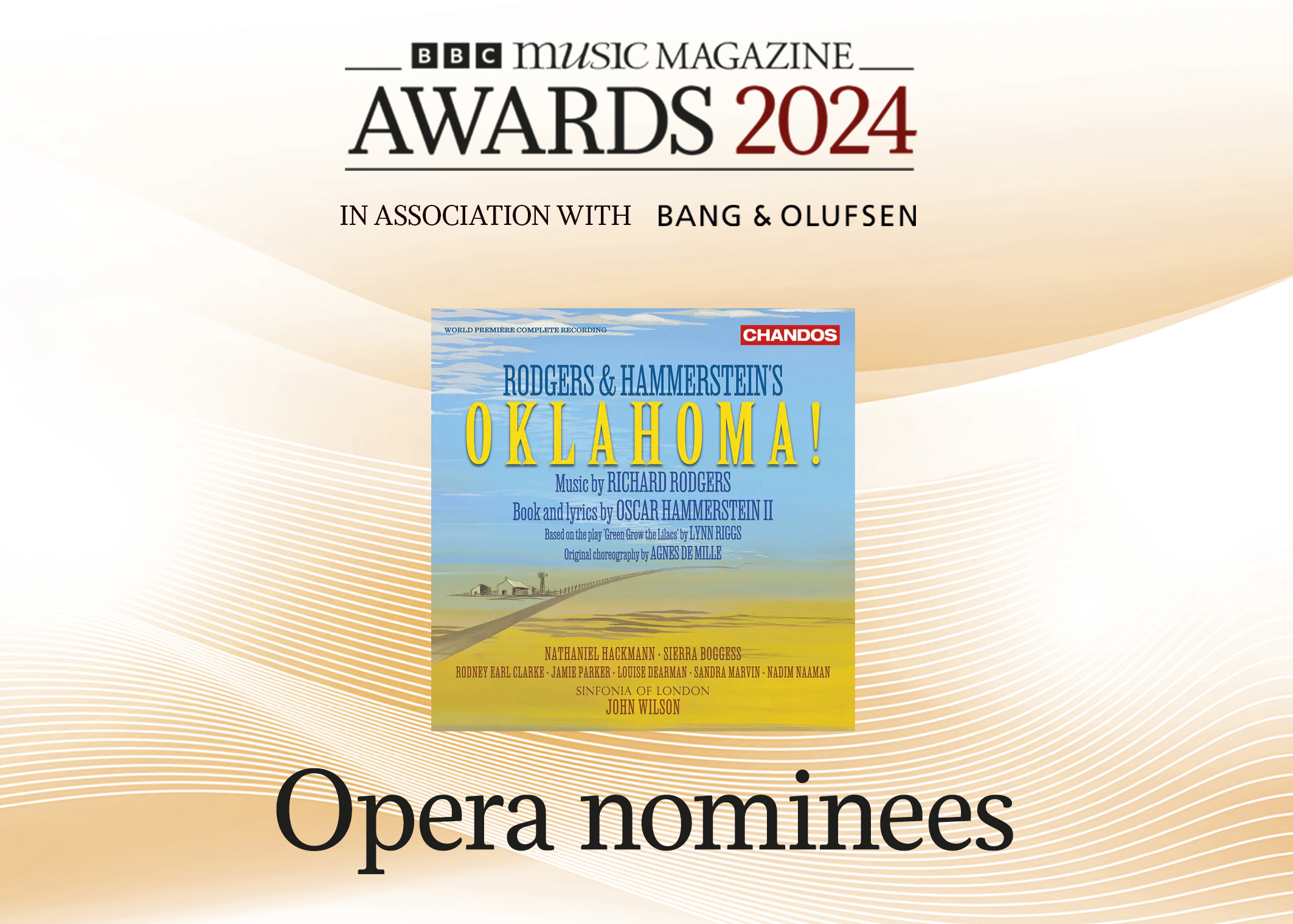

Sinfonia of London win big at BBC Music Magazine Awards 2024

John Wilson and Sinfonia of London’s première recording of the complete original score of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! took home the Opera Award, while the same forces also scooped their fourth Orchestral Award with their album of works for strings by Vaughan Williams, Howells, Delius and Elgar. Described by the magazine’s reviewer as ‘a stunning benchmark for the digital generation’, this recording also went on to win the coveted Recording of the Year.

To say thank for all the BBCMM24 at checkout!

Pictured above from left, Francis Williams, Jonathan Allen, Rosenna East and Ralph Couzens.

Pictured above from left, Francis Williams, Jonathan Allen, Rosenna East and Ralph Couzens.

This Thursday!

Good luck to Sinfonia of London and John Wilson ahead of this week's award ceremony! 'Music for Strings' and 'Oklahoma!' have been nominated in the Orchestral and Opera categories respectively.

Margaret Fingerhut appointed MBE in the 2024 New Year Honours

To celebrate pianist Margaret Fingerhut being recognised for services to music and charitable fundraising why not explore her brilliant back-catalogue.

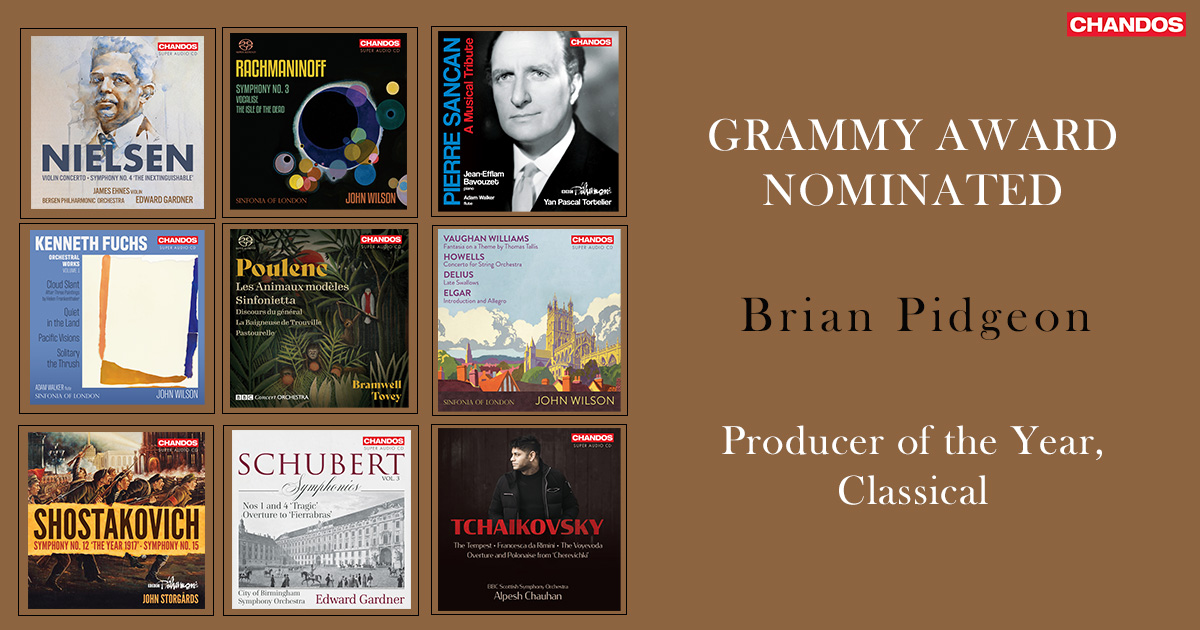

Brian Pidgeon GRAMMY nominated for Producer of the Year!

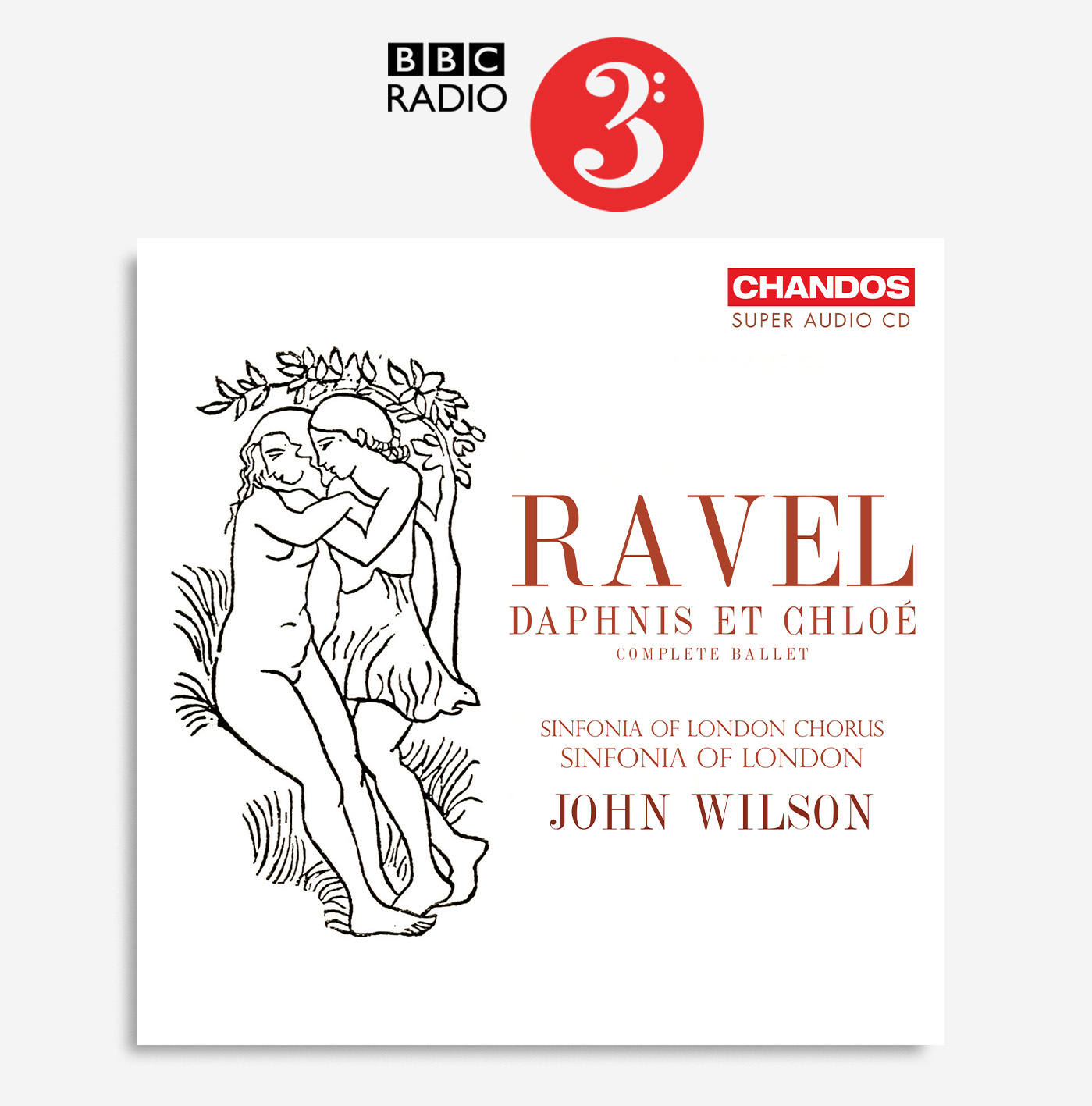

Sinfonia of London's latest album 'Record of the Week' on Record Review!

The new release from Sinfonia of London and John Wilson, Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, was featured on BBC Radio 3's much-loved Saturday morning Record Review show (4/11). We're delighted to report that the new recording was picked as RECORD OF THE WEEK. The show remains available all month on-demand so don't worry if you missed it live, listen here!

This week we will be celebrating the upcoming launch of Oklahoma! from John Wilson and Sinfonia of London at The Savile Cub in Mayfair. This landmark album will be the first full recording of the original Rodgers & Hammerstein score, to commemorate this very special release we have produced a series of limited edition numbered vinlys available to pre-order now! Don't miss this historic album, out on Friday 15th September!

Gramophone Awards Shortlist 2023

Gramophone Awards Shortlist 2023

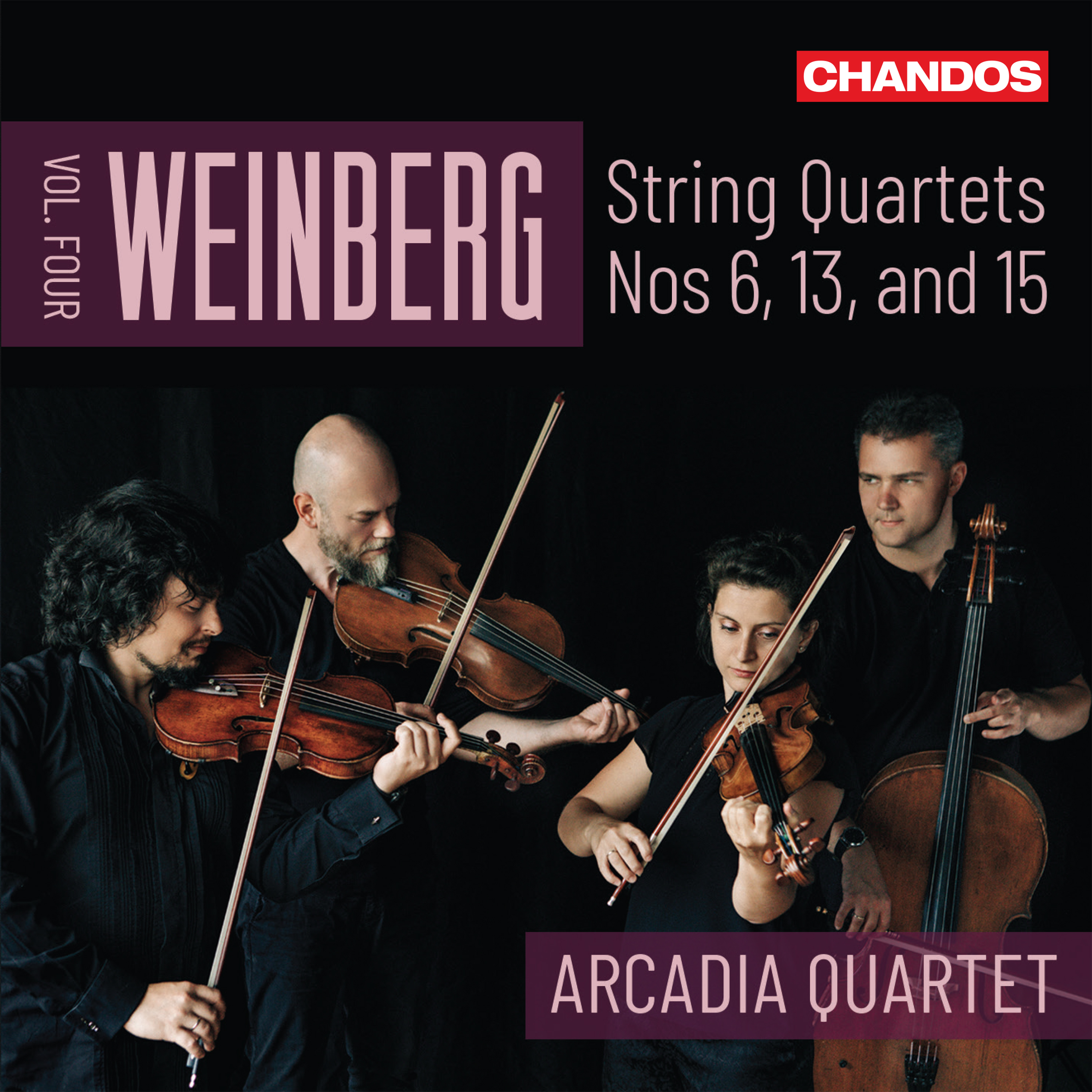

We are delighted to have FOUR albums shortlisted for the Gramophone Classical Music Awards 2023! See the shortlist here, including albums from Kaleidscope Chamber Collective, Arcadia Quartet, and Sinfonia of London.

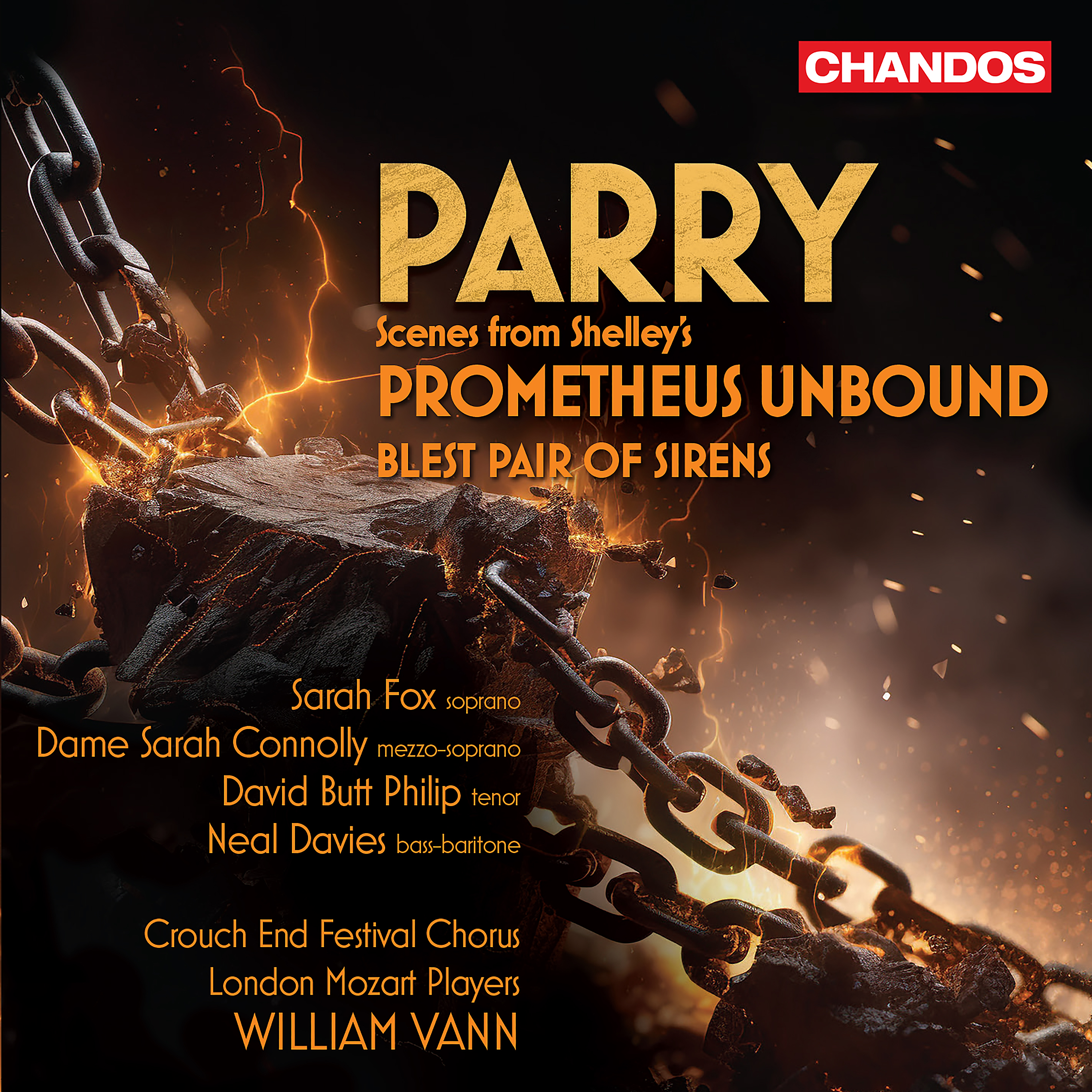

Gramophone Editor's Choice: October

Gramophone Editor's Choice: October

'Parry's compelling response to Shelley's lyrical drama is given a superb performance of real conviction, conduction by William Vann and with a line-up of starry soloists'

'Orchestra of the Year' nomination!

'Orchestra of the Year' nomination!

Our friends and collaborators BBC Philharmonic have been nominated for Orchestra of the Year at the Gramophone Awards 2023!

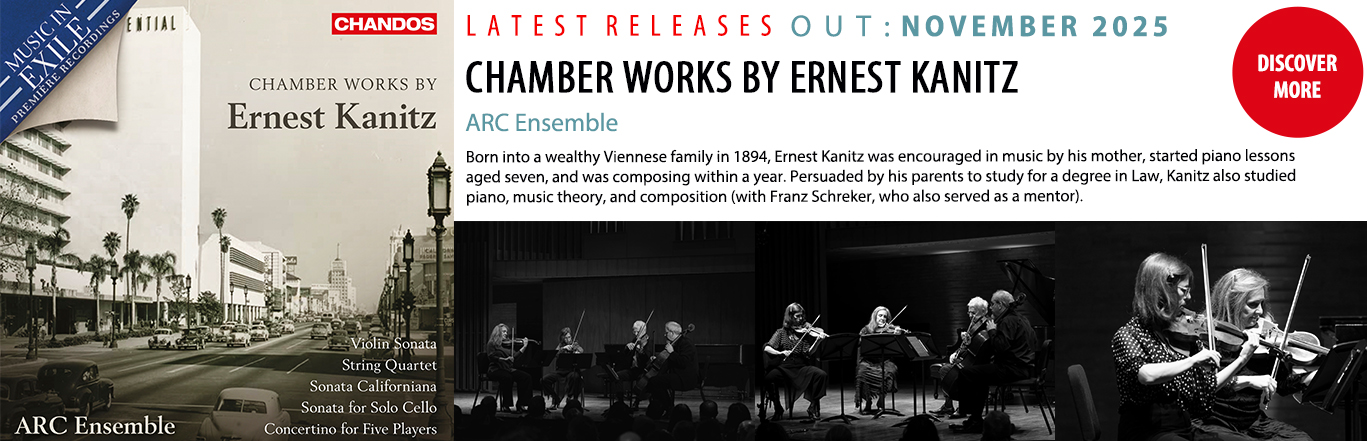

ARC Ensemble

25% discount on ARC Ensemble Recordings

In 2002 Canada’s Royal Conservatory of Music established the ARC Ensemble (Artists of the Royal Conservatory) as the organization’s ensemble-in-residence. In the two decades since, it has become one of the country’s most distinguished cultural ambassadors, earning several Grammy, Juno and OPUS Klassik nominations, and appearing at major festivals and venues around the world. ARC’s repertoire is unique to the ensemble, and is largely dedicated to music suppressed and marginalized under the 20th century's repressive regimes, works the ensemble has researched and reintroduced to the repertoire. The ensemble believes that in neglecting them, we have both silently supported the policies that led to their exclusion, and presented a distorted view of musical history as a result. The ARC Ensemble’s concerts and recordings, have led to a substantial number of extraordinary works joining the repertoire. ARC Ensemble appearances include the Budapest Spring Festival, the Enescu Festival, New York's Lincoln Center Festival, Canada's Stratford Festival, the Concertgebouw, Wigmore Hall and Washington's Kennedy Center. Its “Music in Exile” series has been presented in Tel Aviv, Warsaw, Toronto, New York and London, and its performances and recordings continue to earn unanimous critical acclaim, as well as frequent broadcasts around the world. ARC’s core members are Erika Raum and Marie Bérard, violins; Steven Dann, viola; Tom Wiebe, cello; Joaquin Valdepeñas, cello and Kevin Ahfat, piano. ARC’s Artistic Director is Simon Wynberg, its Honorary Chairman is James Conlon.

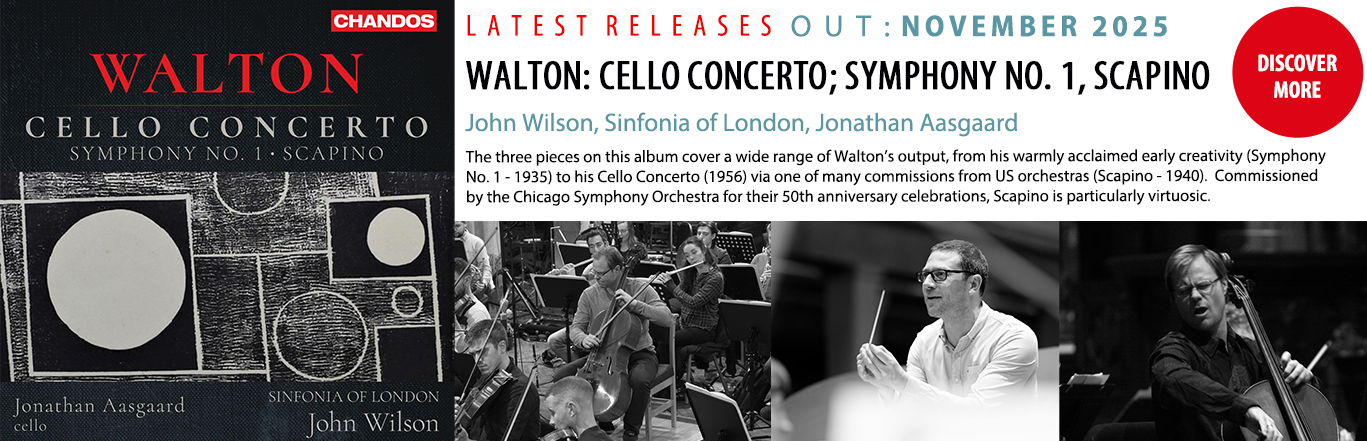

Concerto Choice

'In John Wilson's hands, Walton's Ravelian timbres shimmer and glisten.'

Concerto Choice

'In John Wilson's hands, Walton's Ravelian timbres shimmer and glisten.'

Editor's Choice

'If ever there were a composer and conductor ideally suited to each other, it is William Walton and John Wilson.'

Editor's Choice

'If ever there were a composer and conductor ideally suited to each other, it is William Walton and John Wilson.'

My Wish List

My Wish List

.jpg)

%20carousel%203000px%20digital.jpg)

,%20by%20richard%20hubert%20smith.jpg)

.jpg)

%203000px.jpg)